Around siesta time [...] behind the islands of Capri and Ischia a dark, threatening sky came up, which soon swallowed the sun and covered the whole sky, pushing down the smoke from Vesuvius, so that in the city one began to smell the sulphur. [...] In the leaden sky lightning raged for some time without interruption; the thunder, however, was not yet perceptible; a breath-taking silence added to the ominousness of this approaching thunderstorm. (Fabricius 1934: 2-3)

Together with this violence of nature, Circus Storm arrives in Naples. After the storm calms down, the Neapolitans flock to the circus tent to watch the dazzling performances of artists and animals. These special performances by lions, panthers and aerial acrobats, among others, continue to attract visitors and even become famous. This changes when suddenly an unprecedented winter chill sweeps over the city: the circus loses more and more customers and eventually goes bankrupt. The young and ambitious Rambaldo Fittipaldi sees his chance and decides to help the circus in the hope of making a name for himself as a lawyer.

This is a preview of the novel Leeuwen hongeren in Napels (Lions starving in Naples) (1934) written by Johan Fabricius (1899-1981). In this book, a number of interesting aspects from Italian culture and history come to the fore, to which I would now like to pay some attention.

First of all, the book mentions ‘Il lotto’ once. (69) This is an Italian game of chance played mainly in the South of Italy. The game is similar to the lottery, but to determine the numbers of your ticket you use La smorfia. This is a large book in which all kinds of events, dreams, objects and persons are related to a certain number. Suppose you have just had a bizarre dream or you have experienced something special, then you quickly run to La ricevitoria (the place where you can buy lottery tickets) and get a ticket with numbers based on that event. If you would like to know more about this phenomenon, I recommend you watch the documentary Dreaming by numbers (2006) by Anna Bucchetti (watch the trailer here). This documentary goes deep into the history of Il Lotto. Furthermore, various people explain their reasons for participating in this particular game of chance.

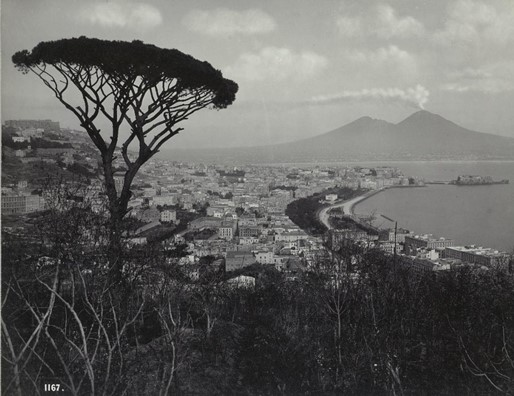

Source: Giorgio Sommer, ‘1167 Napoli panorama’, ca. 1893-1903, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.Second, the book relates to racism and Italian emigration. This theme emerges in descriptions of a group of Senegalese. This group is part of the circus, but is often described as subordinate and ‘different’. This becomes clear at the beginning of the story, for example, when the Senegalese are not given any food that they like and they complain about this to the director of the circus. The leader of the group of Senegalese has just started his plea when ‘the white supreme god’ (the director) interrupts his plea. (16) The cook is then called to account by the director, but he resists and uses the racist term ‘diesen senegalesischen Halbaffen’ (these Senegalese half-monkeys) to describe the group. (16) The fact that there is a separation between the Senegalese and the others is also made clear when Fabricius writes: ‘What kind of an image the Senegalese must have of this world of the whites.’ (163)

Source: Giorgio Sommer, ‘1167 Napoli panorama’, ca. 1893-1903, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.Second, the book relates to racism and Italian emigration. This theme emerges in descriptions of a group of Senegalese. This group is part of the circus, but is often described as subordinate and ‘different’. This becomes clear at the beginning of the story, for example, when the Senegalese are not given any food that they like and they complain about this to the director of the circus. The leader of the group of Senegalese has just started his plea when ‘the white supreme god’ (the director) interrupts his plea. (16) The cook is then called to account by the director, but he resists and uses the racist term ‘diesen senegalesischen Halbaffen’ (these Senegalese half-monkeys) to describe the group. (16) The fact that there is a separation between the Senegalese and the others is also made clear when Fabricius writes: ‘What kind of an image the Senegalese must have of this world of the whites.’ (163)

In addition, the group of Senegalese is described as animalistic, scary and arrogant. Their act is received by the circus audience with the words ‘Ah... ché cosa spaventosa!’ (Ah… how frightening!) (27) Their arrogance comes to the fore when things go very badly with the circus. The Senegalese decide to give their money to Saul the lion tamer, so that he can distribute all the money and food fairly among the remaining performers – however: ‘Afterwards they [the Senegalese] became haughty that he had accepted it, and forced themselves on the keepers and Saul as if they were equals.’ (163) When the Neapolitans, during a bad period for the circus, come to bring food to the hungry circus animals it becomes clear that they regard the Senegalese as animals: ‘These conceited animals [the camels] chewed their flour cakes so calmly and without any noticeable enthusiasm, as if they had been given them every day for breakfast. And furthermore, both young and old regretted that they were not allowed to throw something down the throats of the Senegalese.’ (178)

In short, the Senegalese are seen as different; they are supposedly animalistic and arrogant, with ‘the whites’ as their bosses. At the end of the book, an interesting situation arises in which this idea is put in a different light. WARNING: if you don’t want to know about the end of the book yet, I recommend you skip the next paragraph!

Circus Storm, or what is left of it, is eventually rescued by an American billionaire named Jeffries. His country of origin is described as ‘the land of unlimited opportunity and young billionaires’. (233) Jeffries himself is almost elevated to a god. This becomes clear when the circus artists are waiting in the hall of the hotel for Jeffries to come and sign the contract: ‘How anxiously the simple folk waited in the palace-like hall for the moment when the great man from America would like to come down to them in an elevator.’ (212-213) When Jeffries goes back to his room, it is described as follows: ‘The American had gone to heaven again.’ (214)

Those who first thought they were above the Senegalese now have to be saved by a rich American god. One could say that in this way the behaviour of ‘the whites’ towards the Senegalese is put into perspective.

Sources: Lewis Wickes Hine, 1905, Wikimedia Commons; unknown, 1902, Wikimedia Commons.

But why is it that an American comes to save the circus in Naples? This may be partly explained by history. In the period from 1861 to 1985, nearly 30 million Italians emigrated abroad in the hope of finding a better life. The United States was a popular destination and if you wanted to emigrate from Southern Italy, you usually left from Naples. (Rotondi 2018) Seen in this light, it is almost logical that a rich American should come to Naples to save the circus, and bring the circus to America, the land of unlimited possibilities and riches. It must be said that the circus is not made up of Italians. So, it is not necessarily about the migration of Italians. Nevertheless, given its history, Naples is a logical place for the circus artists to leave for the United States.

Hopefully, this blog about Il lotto and Italian migration has satisfied your hunger for knowledge for the time being. Besides these themes, there is much more to discover in the book Leeuwen hongeren in Napels. But I leave finding these pearls to you, the hungry reader.

Bibliography

Fabricius, Johan, Leeuwen hongeren in Napels, ’s-Gravenhage 1934.

Rotondi, Giuliana, ‘Storia dell’emigrazione italiana’, Focus.it (30 July 2018), https://www.focus.it/cultura/storia/migranti-storia-emigrazione-italiana, consulted on 18 December 2021.