The eighteenth-century travel diary of a captain’s son

On 3 February 1784, a fleet of Dutch ships of the line ran into trouble during a heavy storm at sea. At the time, the ships were in the Golfe du Lyon. Aboard the Noordholland (North Holland), which was under the command of Captain Daniël Jan van Rijneveld (1742-1795) (Westfries Archief), the crew was forced to tear loose the sails to prevent the wind from completely taking control of the ship. After cutting down the sails, the sailors started to tackle the incoming water. For three hours straight, the men pumped out water, after which, unfortunately, some of their pumps broke. The entered water made the ship heavier and heavier and started to push it down. To lighten the Noordholland, two masts were cut, after which the ship’s wheel could also be used again. The sailors did everything they could to save the ship, and with it their lives. However, they could not prevent further damage to the ship: the Noordholland lost parts of the stern and eventually its third and final mast. Additionally, the ship lost the rest of the fleet and the next day even the ship’s wheel broke off. From that moment on, the Noordholland was without sails, masts and a wheel.

Ships of the line in 1783. Source: Carel Frederik Bendorp, ‘Explosie op het schip Rhynland’, 1784, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Ships of the line in 1783. Source: Carel Frederik Bendorp, ‘Explosie op het schip Rhynland’, 1784, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Among the crew of 350 men was Nicolaas Abraham van Rijneveld (1766-1849) (Historisch Centrum Overijssel), the captain’s son, whose published travel diary, Reize naar de Middelandsche Zee (Journey to the Mediterranean Sea) (1803), carefully describes conditions aboard the Noordholland during its nearly three-year sailing trip (from 13 December 1783 to 3 May 1786). In his travel diary, Nicolaas goes into detail about the sea storm that had started on 3 February, in the first months of their voyage. They worked day and night, ‘without any rest or interruption’, to clear the ship of water. (Van Rijneveld 1803: 23) Not that the crew could rest or sleep anywhere; the hammocks washed through the hull of the ship or were used (in vain) to hold back the uncontrollable sea water. The water not only claimed parts of the ship, but also of their provisions.

On 5 February, the tide seemed to be turning: the sailors spotted a ship and after ‘some distress shots’ it came to their rescue. It turned out to be the Vrijheid (Liberty), another ship in the fleet. The masts of the Vrijheid had also broken off. Nevertheless, the wrecked ship tried to assist the Noordholland. Fortunately, a few hours later the Medea also came into sight, another ship in the fleet, which, compared to the Noordholland and the Vrijheid, was in relatively good condition. The Medea managed to tie the Noordholland on a rope, after which it tried to tow the Noordholland to a nearby port, such as Cartagena. The overworked sailors – after all, they had been fighting the water non-stop for three days – also received a new pump from the Medea. ‘This day was […] pleasant’, writes Nicolaas. (27) Nevertheless, the crew was wet, hungry and exhausted – they had lost virtually all their clothing, provisions and energy in the battle.

A carpenter from the Medea managed on 7 February to repair the ship’s wheel of the Noordholland, to some extent. Thanks to the new pump, pumping out the seawater went relatively well. Three days later however, on 10 February, the rope broke. It took the sailors two days to reattach the ships. Unfortunately, a day later the rope broke again, as did the wheel. Due to damage incurred, the Medea was unable to tie the Noordholland to the rope again; the Medea sailed towards the Italian island of Asinara. One day later, on 15 February, the Medea returned from there – where it was presumably (partly) repaired – to then tie the Noordholland back on the rope.

During the night of 15-16 February, the rope broke again, after which the Noordholland lost the Medea for good. At this point, the ship could do nothing else but float. In the morning the sailors caught sight of the coast of Corsica, with distress shots and the waving of ‘as many flags’ ‘as [they] could’ the crew tried to attract the attention ‘of some vessels on shore’. (32) Apart from ‘a few cattle herders’, however, there was no one on shore – ‘which was rocky everywhere’. (33) Their courage sank into the depths: ‘We saw our inevitable downfall, apparently, approaching with rapid grief and had no more hope or expectation to avoid a terrible death.’ (33) Captain Van Rijneveld instructed his crew to move up on deck; if the ship hit the rocks, they could try to swim or float away. Some crew members of high rank and status received money from the captain. They were to use this to care for the castaways, provided they survived the collision. The captain also turned to his son. He ordered Nicolaas to save his own life if he would get the chance to do so; father Van Rijneveld himself would ‘as long as there was or could be anyone left on the ship, not […] leave it himself’. (33) The captain did not want his duty to prevent Nicolaas from leaving the ship alive. Father and son therefore ‘said goodbye to each other, most wistfully’. (33)

With the rest of the crew, Nicolaas prepared for his faith, with ‘their eyes fixed’ ‘on the open grave, which seemed to be waiting for them’. (33) The men said goodbye to each other, were diligently praying, and ‘with hot tears’ wept their wives, children, and other loved ones. (34) As they prepared for a burial at sea, they got a better view of the coast: sand! Not just rocks after all, but sand, and with it the possibility to anchor. Completely unexpectedly, the crew then managed to bring the ship to a halt – thus avoiding Davy Jones’ Locker (i.e., the bottom of the sea). Everyone was ‘transported with joy, so that even the roughest and most insensitive of seamen poured forth tears of joy, and thanked God for such unexpected good fortune, sincerely and fervently’. (36) The recovery of the Noordholland and her crew could begin.

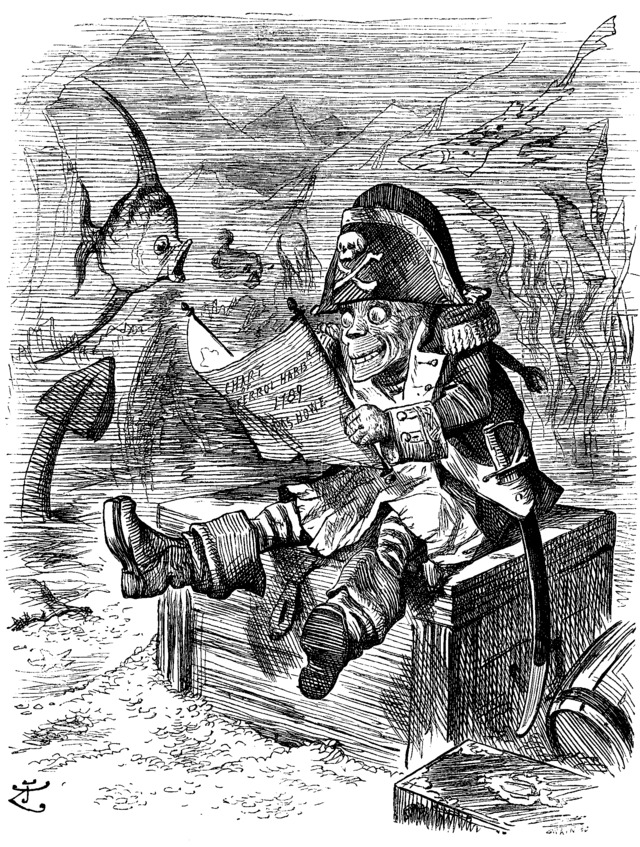

In the early modern period, sailors referred to the bottom of the sea as ‘Davy Jones’ Locker’. They also believed that Davy Jones collected the souls of the people that died at sea in his locker. Source: John Tenniel, 1892, Wikimedia Commons.

In the early modern period, sailors referred to the bottom of the sea as ‘Davy Jones’ Locker’. They also believed that Davy Jones collected the souls of the people that died at sea in his locker. Source: John Tenniel, 1892, Wikimedia Commons.

The journey of the Noordholland is impressive. From the perspective of the captain’s son we can relive this extraordinary journey. Reize naar de Middelandsche Zee offers insight into life on a ship in the eighteenth century. Nicolaas’s travel diary shows how important cooperation was: the crew functions as a living organism and can – in general – rely on the help of both domestic and foreign sailors. The book also provides insight into the appreciation of familial and friendly ties, such as those between a father and his son. Moreover, Nicolaas wrote not only about the sailing route and conditions along the way, but also about the coastal towns along which the Noordholland sailed as well as some inland towns, which will be the topic of the second part of this blog.

Bibliography

Historisch Centrum Overijssel, Zwolle, toegangsnummer 0123, inventarisnummer 7941, aktenummer 232.

Van Rijneveld, N.A., Reize naar de Middelandsche Zee, Amsterdam 1803.

Westfries Archief, Hoorn, toegangsnummer 1702-09, inventarisnummer 107.